Can I Stay There

Inclusive Playspaces are places where everyone should feel welcome and are places high in play value where everyone can get around and feel like they belong- a place to play together and socialize. Guided by the Australian Inclusive playspace programme, this section adds to the previous notes on CAN I GET THERE and CAN I PLAY THERE, and now talks about CAN I STAY THERE. Can I stay there is concerned with the combination of added play value, alongside comfort and considerations such as shelter, toileting or water availability,

An important step in auditing or planning for a playground or playspace, is to consider how diverse children and families will play and stay there longer. Core Principles from the Playability Model that apply include:

- Principle 2: Respect for diversity of age, gender, size, ability, socioeconomic, ethnicity and cultural differences

- Principle 3: Intergenerational spaces: Incorporating amenities as well as play opportunities

- Principle 4: Play value

- Principle 5: Positive approach to risk and challenge in policy and provision

Core considerations listed in the Playability Model come into play here, as these are the aspects that are known to affect the possibility that children and families stay and play longer.

The most common problems that arise include:

- Fencing or lack of a boundary

- Not meeting the needs of the community- where community consultation may not have been carried out.

- Play components lack challenge for progressing play for diverse children

- Poor provision of opportunities to shape and change the environment using loose parts, natural elements, or locally available toys and play materials.

- Poor maintenance and issues of vandalism, and long-term sustainability

There are several things to consider when planning and designing an inclusive playspace, for helping people to make sure they feel welcome and stay longer for play:

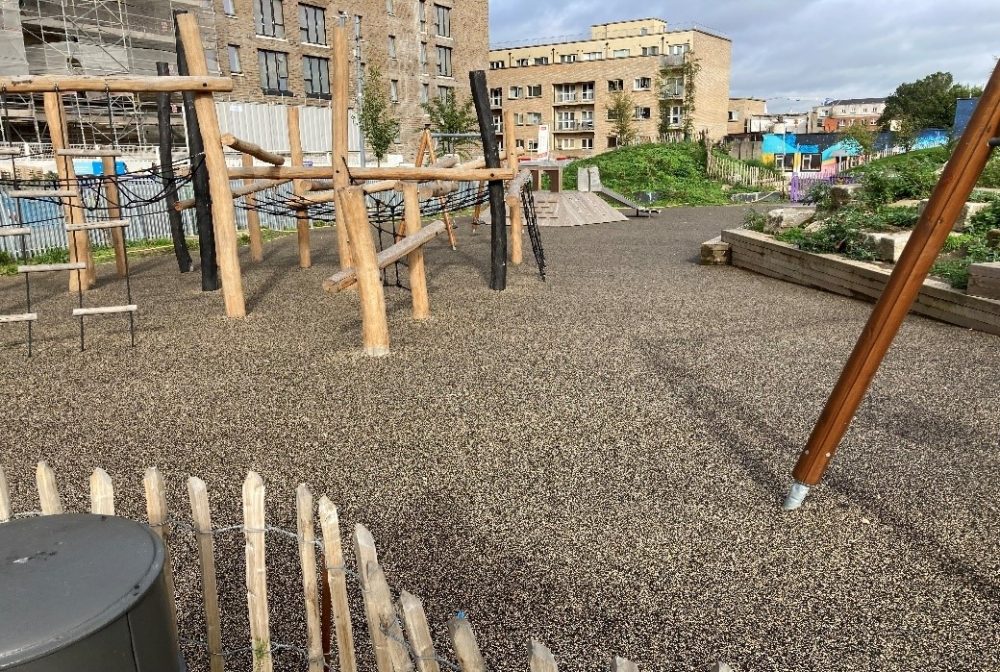

1. Provision of a boundary or fence around the playspace: From a Universal Design approach, the absence of fencing in playgrounds results in a lack of intuitive use and perceptible information. This is particularly relevant for some children with impairments, who do not have the ability to judge where the edge of the playground is, and who may like to run without caution into unsafe areas. Families of children with such disabilities have told us that they travel far to find a playspace that feels safe, and where they can let their child run about safely and freely within the play area (see Figure 1)

Figure 1: example of a low fence around a playspace close to the centre of Dublin, Ireland. It helps establish a boundary without a sense of being segregated from the other parts of the park and streetscape beside it. There are also plenty of benches to sit along the playspace for adults to gather and watch the play.

2. Consider providing sheltered areas: Here in Ireland, rain is more of a problem than heat and sunshine, but a shelter can provide comfort against both! Yet we rarely see a shelter in our community playspaces, despite this request being often raised when we consult with children and families. For some children with disabilities, it takes a lot of work to get organized and come to a playspace. To have to leave suddenly because of bad weather is a big problem. Figure 2 shows a large canopy shelter against the hot and cold weather experienced in Calgary, Canada each year both during hot summers and cold, snowy winters.

Figure 2: example of a shelter provided in a city centre destination playspace, Calgary, Canada

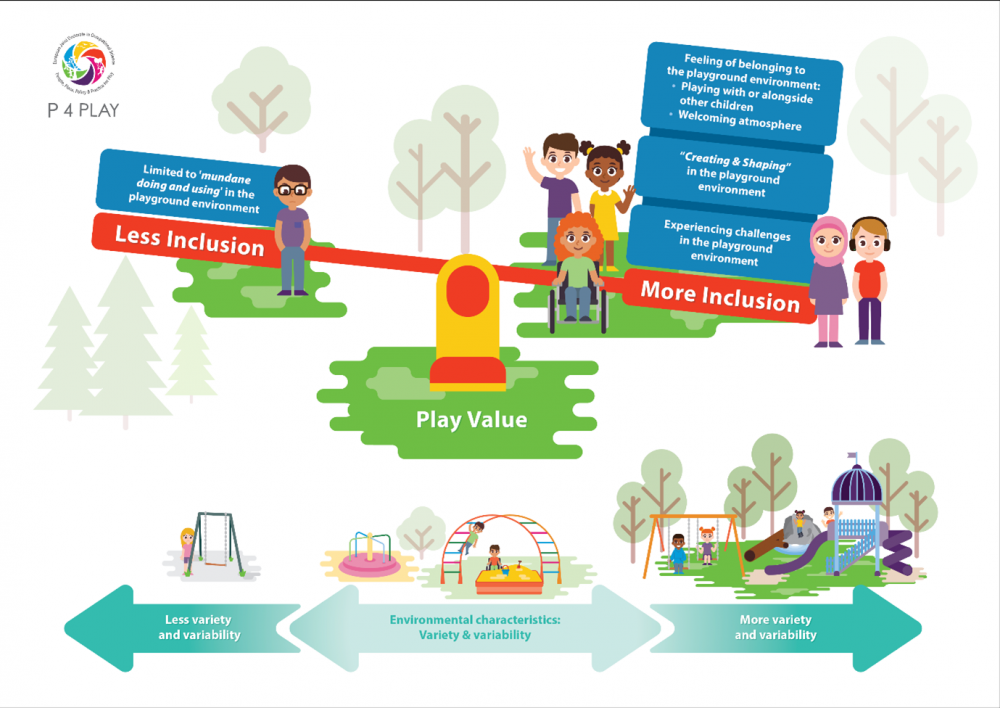

3. Plan for enhancing play value: Planning for maximum play value goes beyond planning and providing large play components. Play value can be really enhanced with the addition of other play opportunities often from what is called loose parts, such as being able to play with sand, water, natural elements such as stones, sticks, ropes. Having tools can help also, such as buckets and spades, empty cartons. Ines Wenger in her review of research on what adds value for children in playspaces, found that it was the possibility to shape and change the playspace that was of most interest to children (see figure 3). For example, building a dam for a water stream, making a hiding space (see figure 4)

Figure 3: Wenger et al’s play value model showing that inclusive playspaces require more variability and variety of play opportunities in a playspace.

Figure 4: Examples of ways to enhance play value

Figure 4a: using topographical features- building a playspace with diversity in slopes and hillocks to encourage running up and down, rolling, and making different spaces for gathering, Cork, Ireland.

Figure 4b: example of a water feature in the playspace, Austria

Figure 4c: example of a digging area with areas to sit alongside as well as inside the pit, Austria

4. Plan for storage if possible: In local playgrounds in particular, it might be possible to have a storage unit for the community to access small play materials such as scooters, shovels and spades, ropes, pieces of wood/sticks to enhance their creative and imaginative play (figure 5)

Figure 5: Two examples of storage solutions in Calgary:

Figure 5a: This first picture is an example of a storage box used in a local community in Calgary, Canada, for families to come and borrow play materials when they visit the playspace.

Figure 5b: This second picture from Calgary city centre is a larger scale storage solution using an old container to store play equipment and also tables and chairs for encouraging the local community to gather and socialise. The playspace is built alongside a raised community garden for local elderly residents, and the container positioned in the middle. Here, the city policy for enhancing intergenerational spaces is evident in how the playspace and broader shared area was designed.

5. Maintenance and sustainability: every playspace needs ongoing work to maintain and sustain it. Playspaces hopefully are places that are well used if valued by the community, and so wear and tear will be an ongoing consideration. It is important to factor this in as the provision of a playspace is only one part of the plan- ongoing maintenance as well as ongoing review and expansion may be needed: for example, new play opportunities maybe needed, such as play opportunities for teens if their play needs are not met within the existing space. Research shows that a well maintained playspace is a desire for children and their families as well as the local community. It also shows that playspaces in communities who were involved in consultation when it was developed, are more likely to be well maintained. Once a playspace begins to age and become less welcoming, people will stop visiting and using it. The sense of wellbeing from going there is lost, and children no longer have fun there. Worryingly, in our P4play research, children tell us that when their local playground is poorly maintained or valued, then they feel like they themselves are also not valued or worth consideration by their city. If we don’t want our children to feel ‘less than’, or of low value, then we must make sure to factor in maintenance and long-term sustainability for our communities.

Figure 6: picture of a playspace in Gdansk, Poland, overgrown and in need of repair

Play value and Universal Design strategies for loose parts play

- Regular and accessible surfacing should lead to all loose parts in the playgrounds.

- Include additional loose parts to maximise variety and stimulate inclusive, imaginative play. Loose parts are natural or man-made and can be manipulated, moved, carried, built and demolished. Loose parts could include for example: items from nature (for example, sticks, logs, stones, leaves), sand (sand tables, sand pits, buckets and shovels for manipulating sand), water (including toys to interact with water), construction materials (for example, logs, tyres, blocks).

- Loose materials should be accessible and within reach (consider, for example, raised tables).

- Include spaces where users can bring loose parts such as balls, trikes, dolls, scooters.